Training the UX Trainers

Developing a repeatable framework for producing clear, effective UX education at scale in a volunteer environment.

The Challenge

An international nonprofit organization relied on software used across many countries, and volunteer software teams located around the world. Volunteers available often had no UX background.

As the person responsible for UX strategy and education across many product teams, I needed to grow a research team from scratch and grow a team of designers embedded in product teams while they were learning.

The challenge wasn't just "how do I train people in UX." It was: how do I build a system that keeps producing capable UX practitioners out of a wide selection of transient volunteers after I step back?

Many of these volunteers were nervous. They were stepping into unfamiliar territory with no background, and they knew it. Feedback that was too harsh, too vague, or too early could kill the interest they'd built. The pipeline had to develop people's skills without crushing their confidence along the way.

The Insight

Strong UX practitioners need two things working together: solid mental models of how and why design works, and the instinct that comes from watching real people use real software. Theory without observation stays abstract. Observation without theory has no framework to build on. The training pipeline I designed deliberately developed both from the start, so that each reinforced the other. This also allowed building theory slowly over time, keeping cognitive load low. Observation and interviews were interactive and interesting, driving interest in theory.

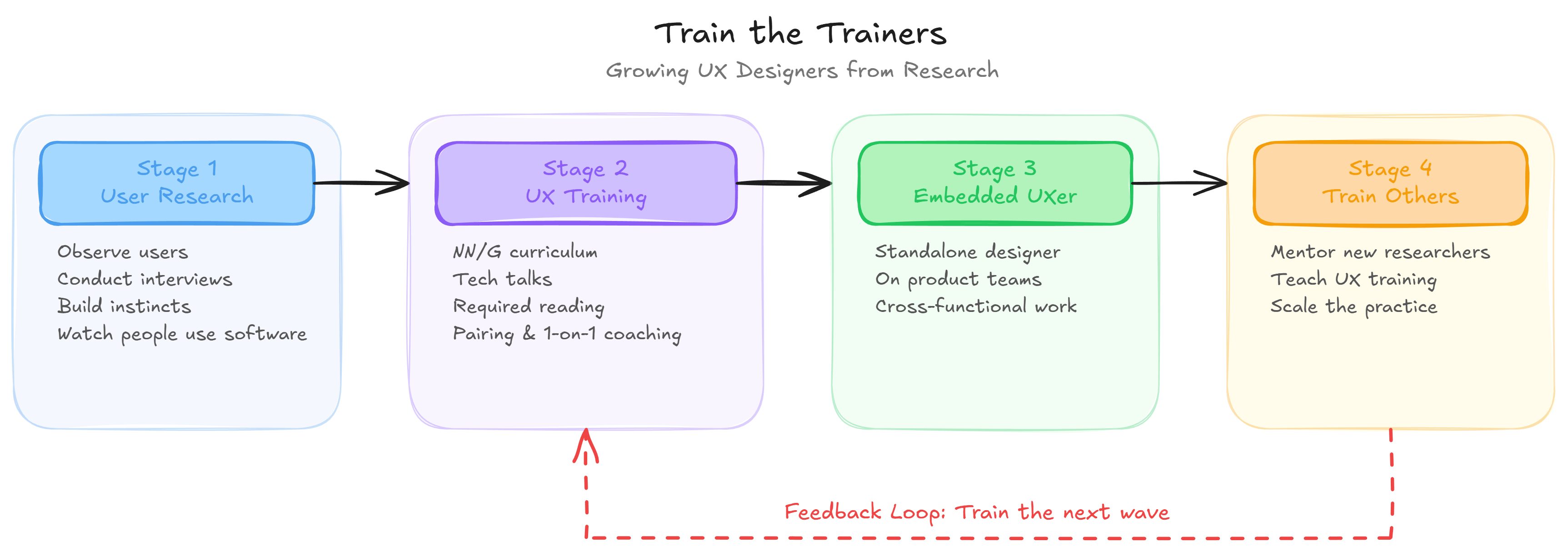

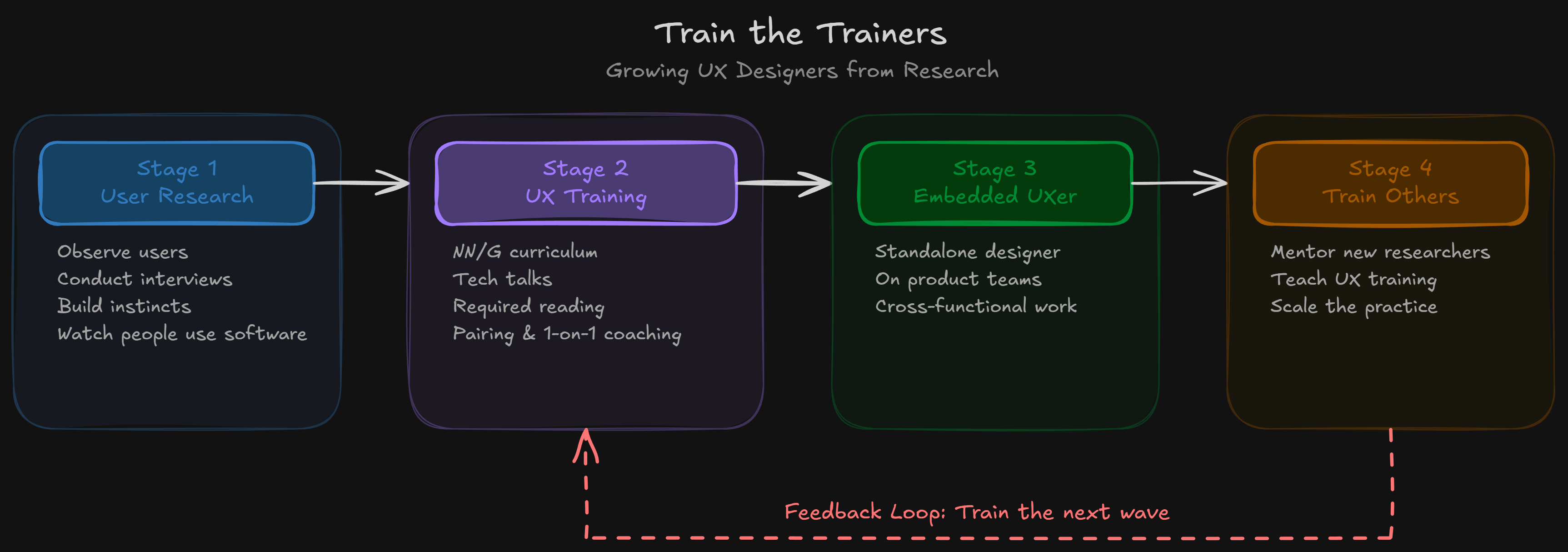

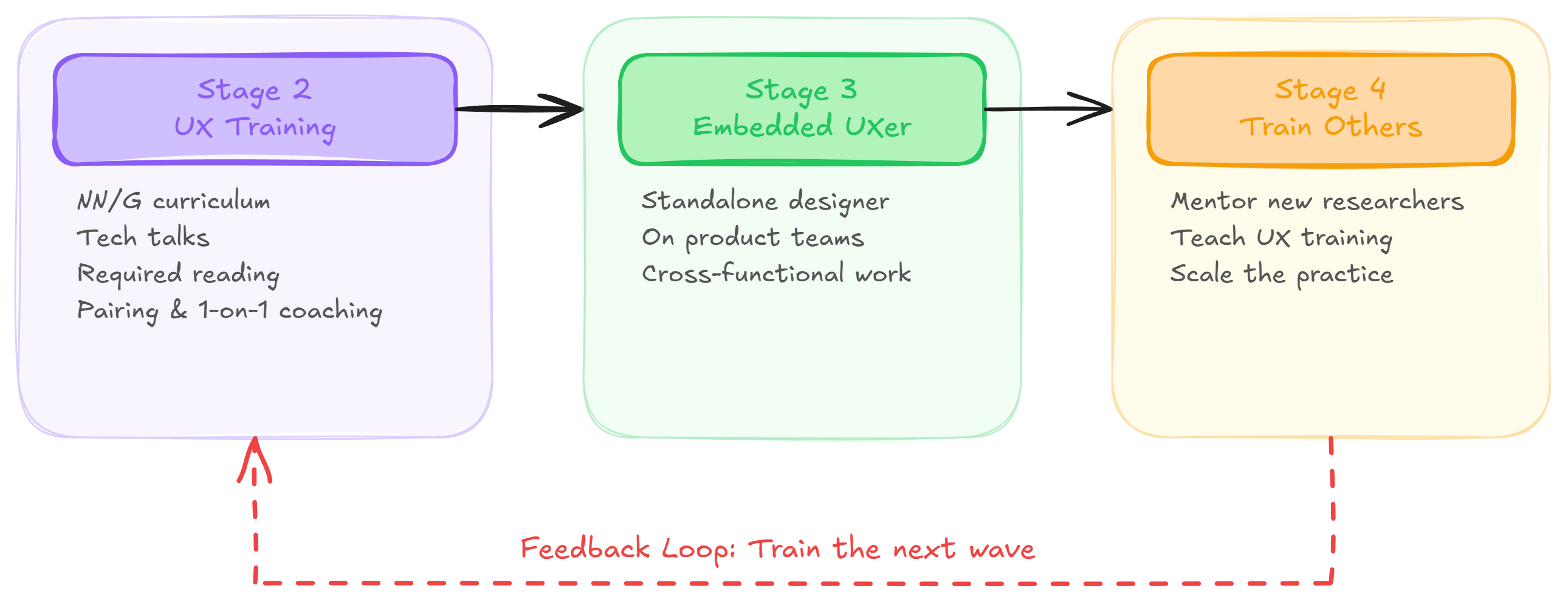

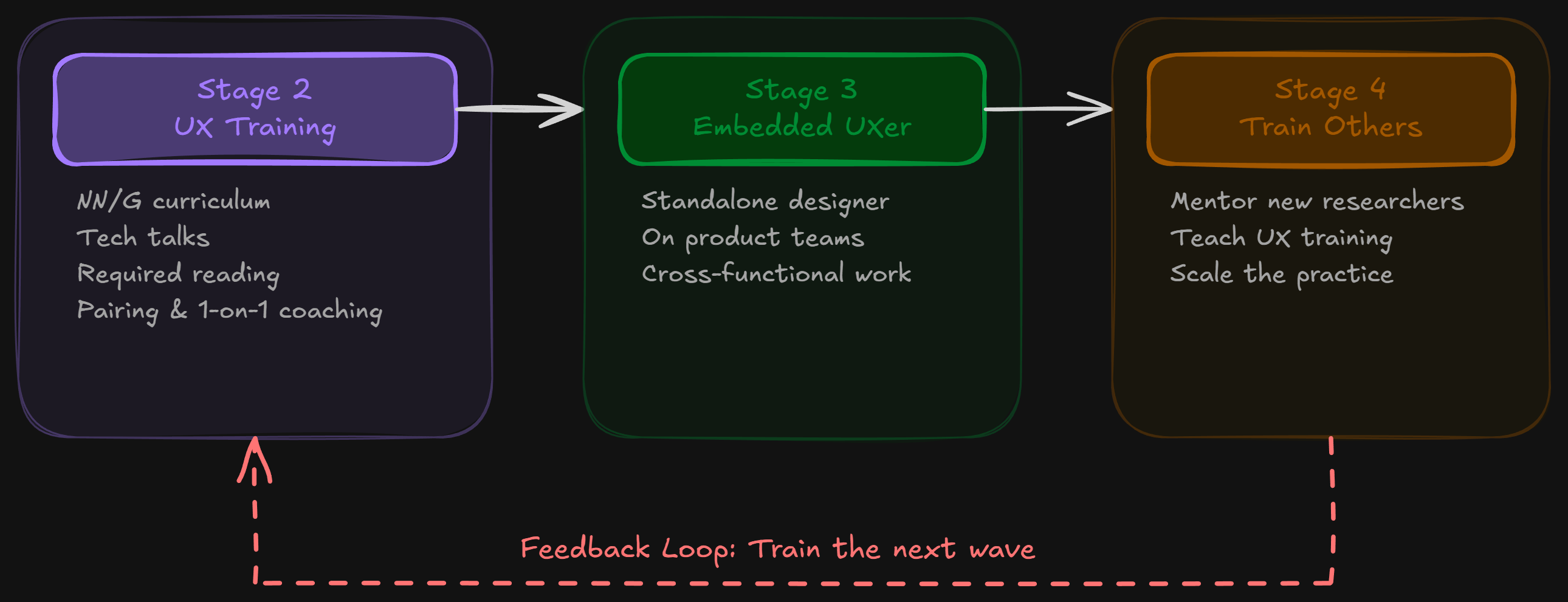

I proposed this four-stage framework to leadership, framed as both a way to build a user research team and a pipeline for developing future UX designers.

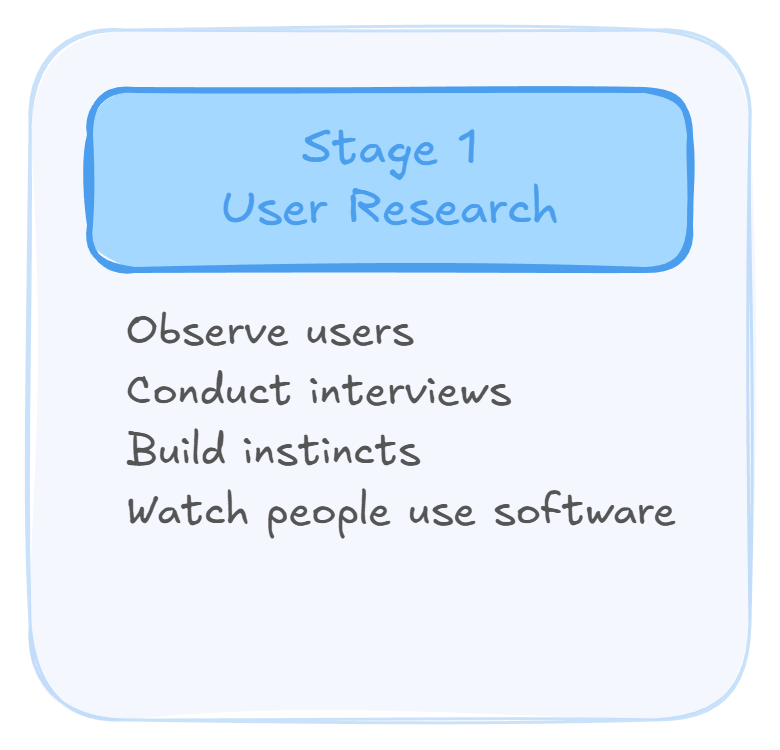

Stage 1: User Research -- Build Instincts Through Observation

Every new team member started here, regardless of their background. They observed usability tests, sat in on interviews, and learned the software by watching real users interact with it. At the same time, they began required reading and coursework that gave them the vocabulary and mental models to make sense of what they were seeing.

This combination was deliberate. When someone watches a user struggle through a task for ten minutes, the heuristic that explains why it's a problem clicks in a way it wouldn't from reading alone. And when they already have the framework from their reading, they can identify patterns during observation that would otherwise just feel like noise.

New team members were also trained on research discipline from the start: how to avoid leading questions, how not to bias participants, and how to stay neutral during sessions. I worked with stakeholders across the organization to build a reliable recruiting process, so that every test reflected real usage patterns rather than convenience samples.

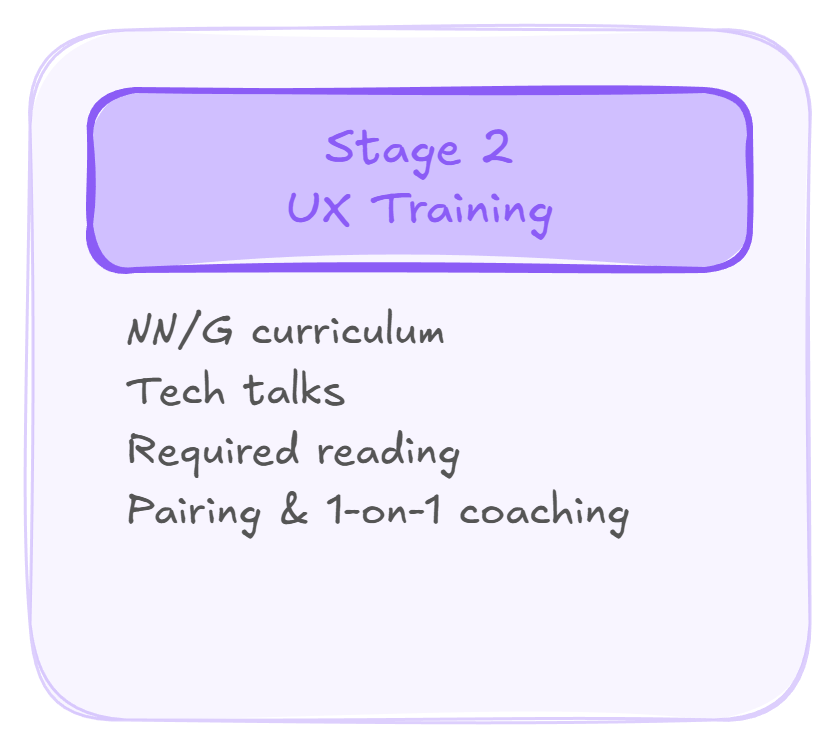

Stage 2: UX Training -- Structured Learning with Coaching

As team members progressed, the training deepened. This stage included curriculum drawn from Nielsen Norman Group resources and established UX literature, along with hands-on workshops and recorded tech talks. I produced many of the talks myself, and reviewed and critiqued ones that others built. Live sessions were recorded deliberately, so that each cohort's training built a reusable library for the next. That library is still in use today.

I designed workshops to put learning into practice. One example: a design studio where team members role-played as stakeholders and designers, working through problem framing exercises together. Reading about stakeholder alignment is one thing. Navigating it in a room full of competing priorities is another.

Running these sessions well required more than knowing the material. I coached facilitators on framing exercises, managing pacing, drawing out quieter participants, and keeping one voice from drowning out the rest.

Each person in this stage was paired with an experienced team member for 1-on-1 coaching. The pairing wasn't informal. It was a structured arrangement with clear expectations for both sides, so that learning was consistent and no one fell through the cracks. A major focus of pairing was teaching people to facilitate core UX activities: design studios, cognitive walkthroughs, and heuristic analyses. Each topic was supported by pre-recorded training videos I produced or reviewed, so pairs had a consistent foundation to work from.

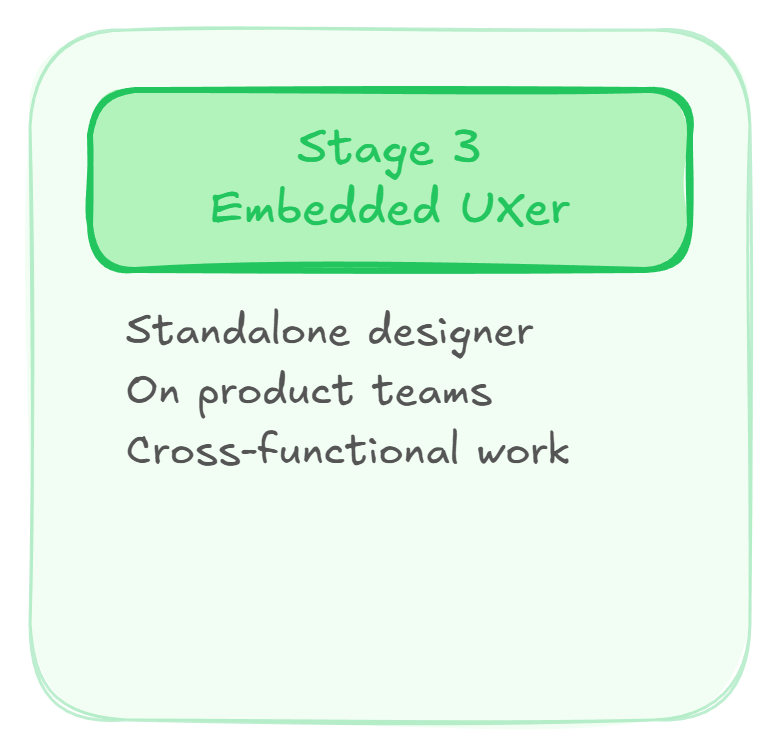

Stage 3: Embedded UXer -- Real Work on Real Teams

The goal of the pipeline was never just academic knowledge. It was to produce people who could do the work independently. In Stage 3, trained team members were placed on product teams as standalone UX designers, working cross-functionally with developers and stakeholders.

This transition didn't happen without support, but the support was lighter than in earlier stages by design. I paired new embeds with experienced UXers for an overlap period, and I reviewed their work directly: design deliverables, research plans, how they ran stakeholder conversations. The feedback was specific but carefully couched to not destroy whatever excitement or momentum the designer had at this point. Every critique connected back to core principles and mental models. The goal was to get them to where they could make good decisions on their own.

The outcome: volunteers who started with no UX background were now functioning as independent designers, making real decisions on real products used across multiple countries.

Stage 4: Train Others -- Scale the Practice

The final stage is what makes the system self-sustaining. UXers who came through the pipeline could become mentors and trainers for the next cohort. They didn't just "help out." They took ownership of onboarding and coaching new team members.

Mentoring someone to teach is different from teaching them to design. When a new mentor paired with a student for the first time, I watched their initial sessions and gave detailed feedback afterward: how they framed exercises and pairing work, how they managed pacing, whether they let participants struggle productively or jumped in too early. Over time, as they began to also help entire teams engage in UX practices, I coached them on subtler skills: reading the room, handling a dominant participant without shutting them down, and knowing how to couch UX insights to tell convincing stories to stakeholders.

New mentors were often as nervous as the people they were training. The critique had to be honest enough to improve their teaching and careful enough not to make them dread doing it again.

As the pipeline grew, training had to stay consistent without me in the room. I built two kinds of materials: structured session plans that gave new mentors a clear sequence to follow, and flexible reference guides that experienced mentors could adapt to their own style. Quality couldn't depend on any single person's instincts.

I kept a close eye on whether the training was actually working: talking to learners, watching mentors in action, and reviewing whether people could apply what they'd learned when it counted. When something wasn't landing, I figured out whether the problem was the material or the facilitation, and fixed it.

For example, I found that teams at times became uncomfortable with technical design terms that new practioners began to use via their training. It became a friction to communication and collaboration. So we did two things: opened live UX tech talks to all team members (not just designers) and taught designers to adjust their vocabulary for their audience, whether developers or stakeholders. The curriculum improved iteratively through that process.

This stage is the feedback loop, and the most important aspect to make the process self-sustaining. Stage 4 feeds back into Stage 2: each generation of trained UXers becomes the teaching infrastructure for the next. The system no longer depends on me. It runs today, years after I built it, continuing to bring in people with no UX background and develop them into capable practitioners who then train others.

The Outcome

The research team grew from nothing to 10 active researchers. Several of those researchers became UX designers. Several of those designers became trainers. Over 30 people have moved through the pipeline over eight years.

Over time, teams facilitated design studios, conducted cognitive walkthroughs, and produced heuristic analyses that directly shaped product decisions. Dozens of enterprise applications were delivered with usability issues identified and addressed through testing before each release. This led to measurable usability improvements and increased stakeholder and user satisfaction across tens of thousands of users.

Because designers were exposed to research from the start, research-driven decisions became the norm. This held true across everything from large-scale usability studies to weekly hallway testing.

Team leads and stakeholders now began to ask "aren't we going to test this?". I know of no better statement to the effectiveness of the approach than non-designers requesting user research.

The most significant outcome, however, wasn’t any single deliverable or artifact. User research and UX became an intrinsic part of the software development lifecycle. The organizational culture shifted toward researched design. That shift is still in place today, and the pipeline is still running.